Not quite the same feeling and fun as a road trip, but fun enough.

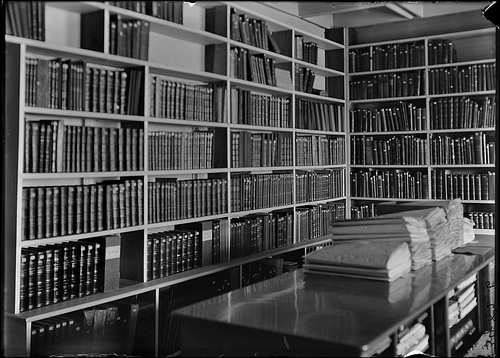

Yeah, archive work! Yeah, Germany! Yeah, yeah archive work in Germany! So I just spent the last two weeks in Germany (by myself, not so yeah) doing some archival research for the dissertation. Here are some thoughts on the trip.

1. Internet!

Make sure you have a good internet connection where you will stay. I booked a decent hotel with Internet included, and free breakfast. The only problem is, the connection to the Internet is spotty at best. I have to get a new user/pass combination to connect to the Internet every 24 hours, too. It’s so frustrating to want to communicate, but not be able to. Especially when you’re trying to get in touch with family back home. So, do some research and hope you get lucky. Also, it is important to know any quirks about the Internet in the country you go to, if going out side of the USA. In Germany, they use 13 channels for their routers, in the USA we only use 11. So if your place of stay uses channel 12 or 13, you’re almost out of luck. You can pick up a relatively cheap USB wireless adapter in the country that should get you all of their available channels. But you will most likely have to find some place with Internet to download software. Enter in the great Internet hubs scattered throughout the world: Starbucks and McDonalds! Even BurgerKing has Internet available. Find out where they are and use them.

2. This is only a test.

Don’t get your hopes up too high for your first trip. I kind of went on this trip with the attitude that it would be a test run of a later real trip. This was possible because I know that I’m coming back in a few months. If you don’t know if you’ll ever go back, then you need to do a lot of background research and contacting before hand. I had scheduled to go to the archive Tuesday through Friday the first week and Monday through Thursday the second week. The first day ended up being a get settled day; exchanging money, finding my way around, finding the Starbucks for Internet, etc. It often felt like I was wasting time, but if you know you are going to go back, then it is time well spent to get your bearings and figure things out. I lived in Germany for two years, but that was a life time ago (like 15 years ago). So I am a bit rusty on speaking German, and German customs, and such. Luckily that mostly all came back easily.

3. Talk to me.

Talk with your contacts before leaving home. Or email them. Let them know exactly what you want to do, what you want to research, where you are going to look, etc. They can save you lots of time. I had one contact at the University of Freiburg, Professor Ulricht Herbert. I met with him twice, and he gave me sound advice. I should have emailed him more often before hand, but nothing really beats face to face contact anyway. My one contact here has turned into two or three. He also helped me realize I am trying to do too much in my dissertation. As it stands, its really a life’s work project. Going through the sources helped me understand that too. There is just way too much for me to be able to grasp it in two years time (my goal). Instead, I’m going to scale back and only cover one tunnel project, and cover that in depth. The reason there is no all encompassing history about the underground projects from World War II is because it was a huge project. Basically the whole of the German economy was turned to focus on these projects towards the end of the War. There is just too much to understand, too many documents to go through, and too much to grasp before this history can be written. That’s why nobody has done it, yet. It would take lots of financing and lots of time. Dr. Herbert suggested four years of work, but only after I had perfect understanding of German, have read all that has been written on the subject so far, and had an intimate grasp of Germany in World War II. That ain’t gonna happen in two years when I have a full-time job, a family, and no financial support. Perhaps that will be my ongoing project as a professor…

4. I’ll make a note of that…

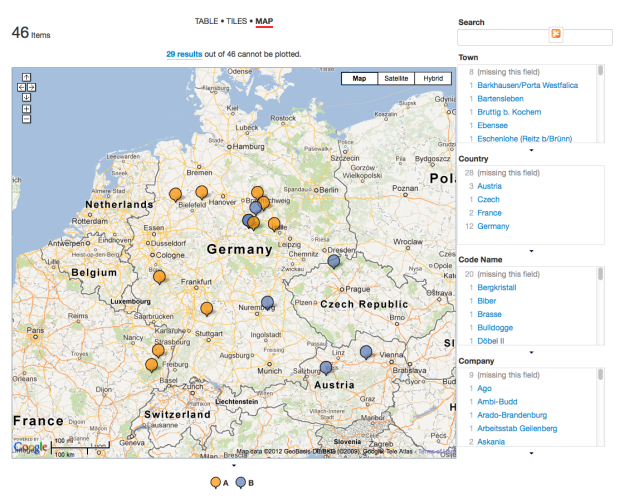

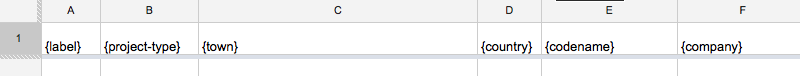

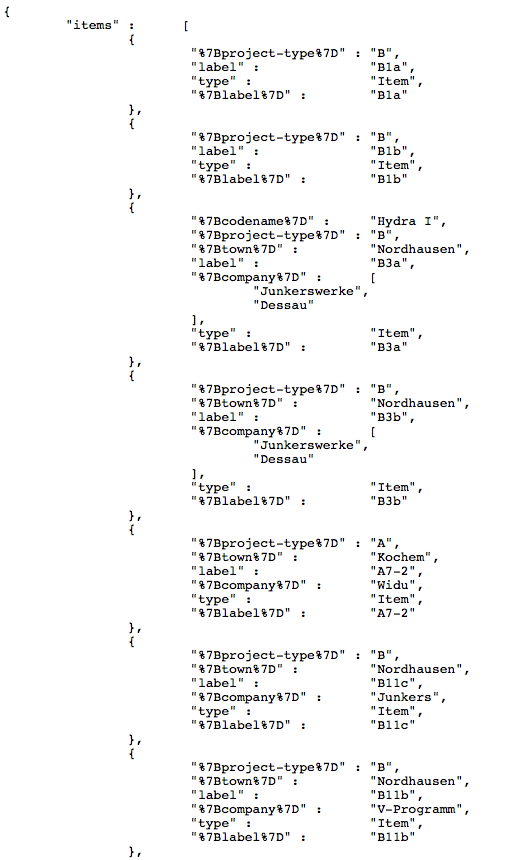

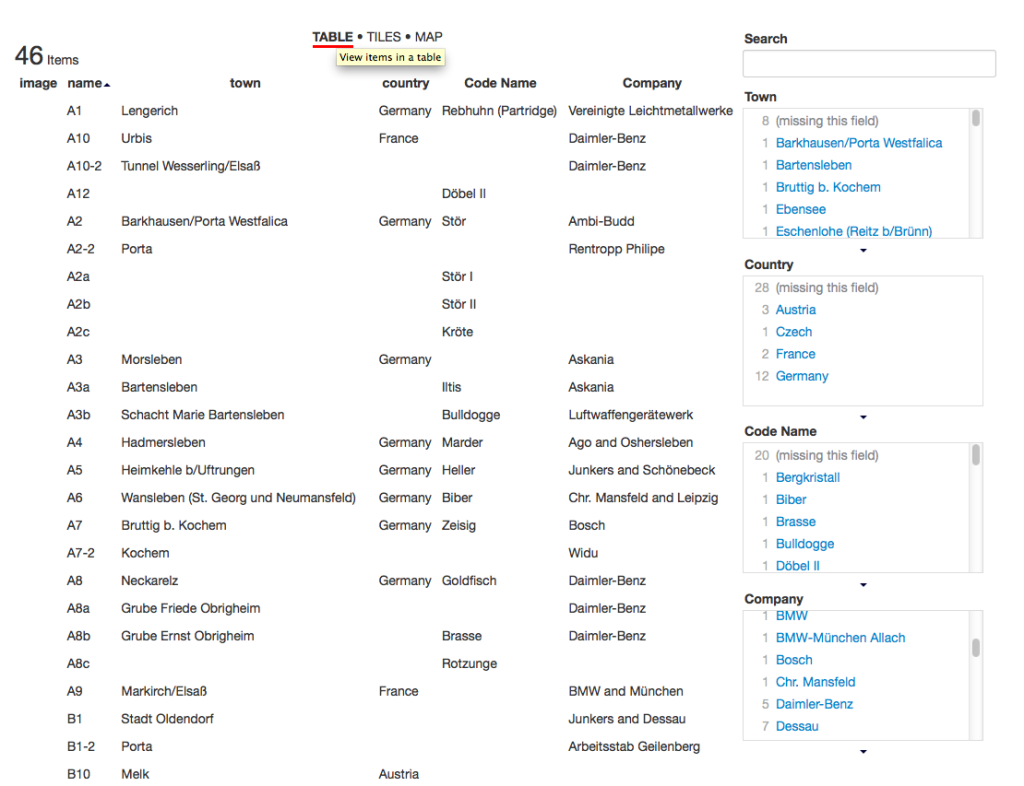

Figure out a good note taking routine. I have several hundred documents digitized from another archive already, and figured out a good naming scheme for them. I have a spread sheet for taking notes on each file, and for later import into Omeka for an online archive. This time around was a little different. The Bundesarchiv-Militärarchiv in Freiburg had lots of documents for me to go through. Whereas before it was one collection/folder in one archive, I now had many collections/folders in one archive. So I had to figure out something a little different. I also didn’t have enough money to make digital copies of any of the records I found. It turned out that I didn’t need to make any, but that should be budgeted and planned for as well. There were a handful of documents that I wanted copies of, so I just transcribed them into a word processing document. I thought about making them plain text documents, but ran into a few formatting issues. I chose to make them LibreOffice (OpenOffice) Text documents, because there will always be a program that can open those, and that program is free. Of course, any program nowadays can open Microsoft Word documents, too, and there is no fancy formatting, so that would work fine too. One of my greatest struggles so far is keeping the documents in place chronologically. So my naming scheme for the files takes care of that. Start the name of the file with the year, then month number, then day number (YYYY-MM-DD), and the documents sort themselves! The file viewer (File Explorer for Windows or Finder for Macs) will usually sort by alphabet, so there’s nothing to it. Another thing I did was to go through the documents as quickly as I could. If It looked like it was helpful, I jotted notes about it, or quickly transcribed it. I will be able to go through the notes and transcriptions later to make sense out of them. That leads into the next point.

5. Plan it right.

Leave a day on either end for miscellaneous things. I unintentionally had a whole day with nothing to do. I was finished with the archives on Wednesday, and didn’t need to leave until Friday. That left me with the whole day on Thursday to tie things up and get ready to leave. I did some laundry, packed my bags and wrote this. It’s also a good time to go through the notes to make sure you don’t forget anything.

6. Enjoy!

The final tip is to just enjoy the time. If you’re in a foreign country, take a day to go see the sights. I had a weekend where the archive was not even open, so I spent the day walking around the awesome Altstadt (the oldest part of town, buildings from the 1400’s!). If you have funding for your trip, just think, who else gets paid to go look at old documents. Man, history is great! 🙂

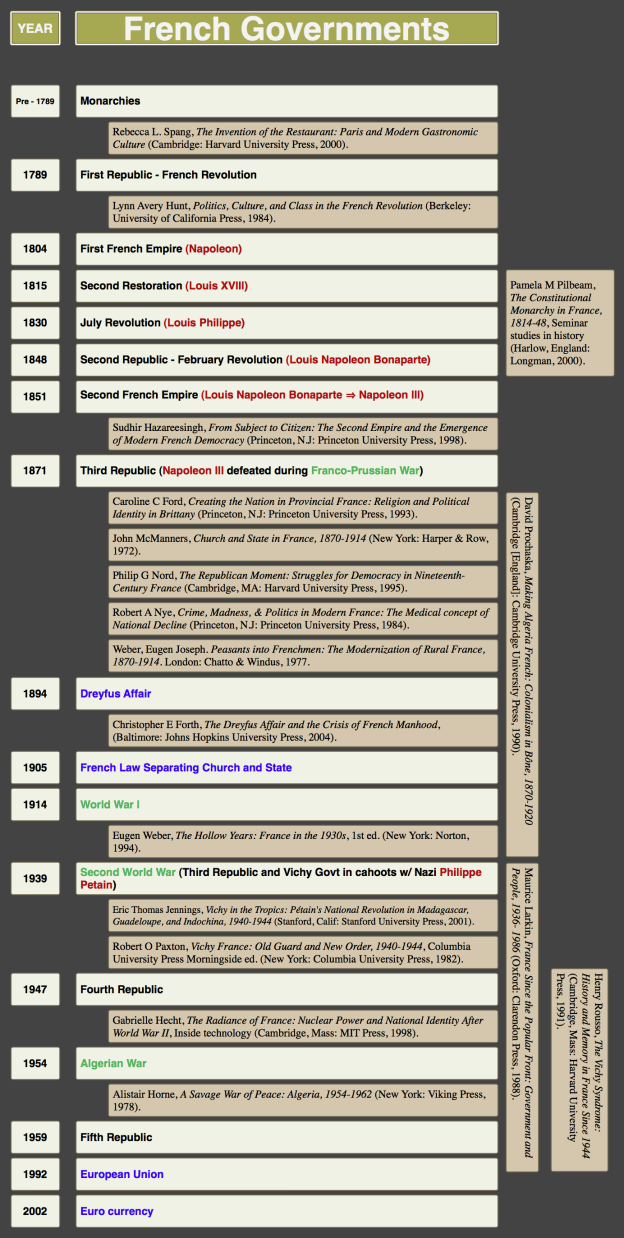

Zotero

Zotero Scrivener

Scrivener