This is an essay I wrote for a Directed Readings course in Fall 2009, with Marion Deshmukh.

The Sonderweg of German History

Before 1940s there was a positive Sonderweg thesis that promoted favorably the differences of Germany from other Western nations.[1] This is similar to what every nation does, showing their best side, why they are better or, in a good sense, different than other nations. These are typical self-promotion tactics that help one feel good with ones’ self, and to help others see the virtues they would like them to see. This thesis is more appropriately termed the “German divergence from the West” in English. Sonderweg was mainly a derogatory term used by its critics.

After 1940, the positive Sonderweg was no longer developed or used. A critical Sonderweg took the place of the positive reflection of German history, with the new one attempting to answer one prominent question; How did Germany produce a society and political atmosphere where National Socialism could come to power? Proponents of this Sonderweg thesis have been Ernst Fraenkel, Hans Rosenberg, George Mosse, Fritz Stern, Karl-Dietrich Bracher, Gerhard A. Ritter, Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Heinrich August Winkler, Helmut Plessner, Leonard Krieger, Kurt Sontheimer, John Maynard Keynes, Fritz Fischer, Wolfgang Mommsen.[2]

Those who argued for a critical Sonderweg put forth the following points for seeing Germany’s special path to National Socialism.

- Sonderweg proponents were cautious about asserting a “necessary relationship between long-term developments in German History and the triumph of National Socialism,” but in the end were specifically looking for peculiarities in German politics that hindered a liberal democracy from developing.[3]

- Germany had a relatively late attempt at creating a nation state. France and the United States of America formed, or attempted to form, a nation in the late eighteenth century. It was nearly one hundred years, finally in 1871, that Germany was able to form a federal government.

- Sonderweg proponents hearken back to the Kaiserreich government’s oppressive practices that limited parliament and caused what parties that did form to be rigid and fragmented.

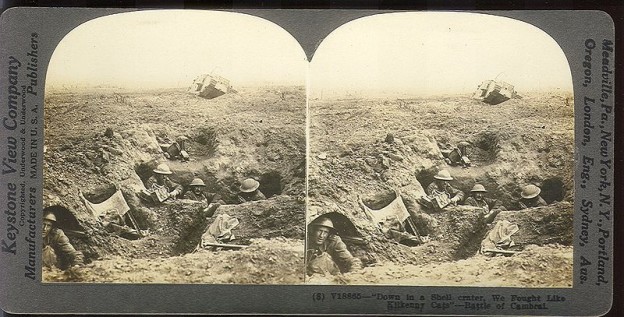

- German defeat in World War I is seen as an important part of the German Sonderweg. The devastating defeat in the First World War left German confidence in tatters. Coupled with the limiting and demeaning restrictions of the Versailles Treaty, Germany seemed anxious to prove to themselves and Europeans that they were a nation of worth. The defeat also led Germany into a new phase of government different, full parliamentary constitution with no monarchy or empire.

- Germany’s political culture tended to be conservative. This made it difficult for liberal parties to be effective.

- The “Junkers-the large agrarian landowners east of the Elbe River” (similar to the English gentry) retained much of their power. Whereas other nations had developed a parliament with representative leaders, much of Germany’s power still lay with landed aristocrats.

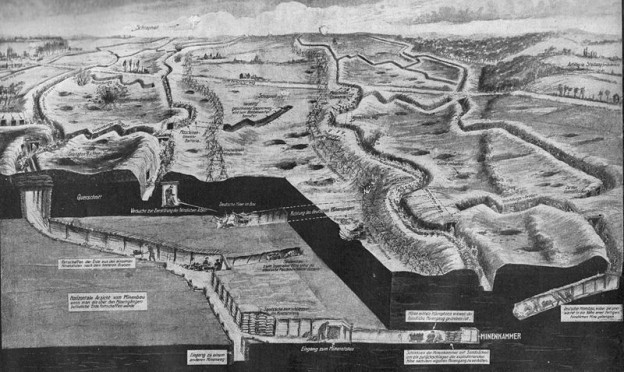

- Bismarck’s forming the nation-state with “Blut und Eisen”–“blood and iron” which put emphasis on the military, and left them unchecked by parliament. This gave a militaristic approach to German government that lasted through the Weimar Republic and into National Socialism.

- The unbourgeois-ness of the bourgeoisie. They never really revolted against the aristocratic society and political culture. There was no middle class of people to rise up in rebellion as there were in other Western states. As a result Germany was left without a tradition of successful revolutions and a history of top-down reforms. Combined with pressure from the peasants, the middle classes were politically weak.

- Germany experienced a strange mixture of social and economic modernization and industrialization and capitalism on one hand, but maintained the old power relations, pre-industrial institutions, and cultures. It was an odd combination of old powers, cultures and organizations in charge of new social and economic conditions and ways of production.

- All of these “long-term patterns” came to a head with the “short-term factors” of 1920s and 1930s, and help to explain the collapse of the Weimar Republic and rise of National Socialism.[4]

“In a nutshell, the critical Sonderweg thesis claimed to indentify long-term structures and processes that, under the influence of numerous other factors (from the consequences of defeat in World War I through the class conflicts of the 1920s to the peculiarities of Adolf Hitler’s personality), contributed to the collapse of the Weimar Republic and the triumph of National Socialism”.[5]

Historians opposed or critical of the Sonderweg have based their critiques partly on methodology. Opponents to the Sonderweg thesis have been Thomas Nipperdey, David Blackbourn, Geoff Eley, Ernst Nolte, Jürgen Kocka, François Furet,Friedrich Meinecke.

Their opposition consists of the following points:

- There are several historical continuities to be seen in German history. For example the Kaiserreich is also a prehistory of the Federal Republic of Germany. This line of reasoning suggests that as National Socialism fades farther into the past, it becomes less of a clear case that the collapse of the Weimar Republic led to National Socialism. Supporting a Sonderweg assumes there is a “normal path” that Germany could have taken. To define what a “normal” path is, is much to subjective a “value judgment,” and the belief in the superiority of “the West”.[6]

- A research in Bielefeld has shown that the aristocratic influence (or dominance) over the middle class was no greater in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Germany than in other western European nations. International comparisons have shown, contrary to Sonderweg hypothesis, that the educated German middle class was “strong and clearly contoured”.[7] It was a widespread European trait for the bourgeois to turn from liberalism in nineteenth century.

- The Kaiserreich did show signs of modernism. It was “full of modern dynamism, for example in the areas of science and scholarship, art and culture”.[8]

- Intensive recent research seems to point to National Socialism as a modern phenomenon, rather than the results of past traditions.

Some core aspects of the Sonderweg have been supported, though, through recent research in three ways:

1. Three of the basic developmental problems of modern societies showed themselves at the same time only in Germany. 1) Formation of the nation-state, 2) decision to have a constitution (parliament) or no, 3) issues with society brought by industrialization. Other countries dealt with these individually, that is, with generations, or at least decades, of time in between to iron out difficulties.[9]

2. While issues with the middle class, the bourgeoisie, cannot be discounted, they did have less of an effect on Germany society than in other European countries.[10]

3. Germany had a “bureaucratic tradition” of a strong authoritarian state. Such power in the hands of the state blocked parliament from functioning, provided effective services to the people, and weakened middle class liberalism. When a democratic government finally did have power, after World War I in the form of the Weimar Republic, the inability of the leaders to provide a stable economy and society meant Germans were eager, or at least willing, to go back to a strong authoritarian state. Important to realize, though, is that the rise of National Socialism should be seen separate from the fall of the Weimar Republic. National Socialism was too new to have broken apart the Weimar Republic; it merely picked up the pieces.

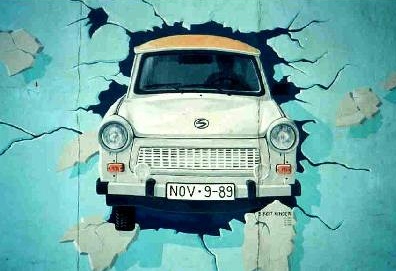

With the Federal Republic the Sonderweg ended for West Germany. It became a “normal” western nation. East Germany, continued the Sonderweg, much altered of course, until its collapse in 1989-90.[11]

Sonderweg Bibliography

Proponents

Bracher, Karl Dietrich, ed. Deutscher Sonderweg, Mythos Oder Realität? München: R. Oldenbourg, 1982.

Browning, Christopher R. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. 1st ed. New York: HarperPerennial, 1998.

Fischer, Fritz. Griff Nach Der Weltmacht: Die Kriegszielpolitik Des Kaiserlichen Deutschland 1914-18. 2nd ed. Düsseldorf: Droste, 1962.

Fritzsche, Peter. Germans into Nazis. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Goldhagen, Daniel Jonah. Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. 1st ed. New York: Knopf, 1996.

Kocka, Jurgen. “Asymmetrical Historical Comparison: The Case of the German Sonderweg.” History and Theory 38, no. 1 (February 1999): 40-50.

Krieger, Leonard. The German Idea of Freedom; History of a Political Tradition. Chicago: University of Chicago Pr, 1972.

Mommsen, Hans. Alternative Zu Hitler: Studien Zur Geschichte Des Deutschen Widerstandes. München: Beck, 2000.

Mommsen, Hans, ed. The Third Reich Between Vision and Reality: New Perspectives on German History, 1918-1945. German historical perspectives v.12. Oxford: Berg, 2001.

Mosse, George L. The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. New York: Schocken Books, 1981.

Plessner, Helmuth. Die Verspätete Nation; Über Die Politische Verführbarkeit Bürgerlichen Geistes. 2nd ed. Stuttgart]: W. Kohlhammer, 1959.

Rosenberg, Hans. Bureaucracy, Aristocracy, and Autocracy: The Prussian Experience, 1660-1815. Boston: Beacon Press, 1968.

Sontheimer, Kurt. Antidemokratisches Denken in Der Weimarer Republik; Die Politischen Ideen Des Deutschen Nationalismus Zwischen 1918 Und 1933. München: Nymphenburger Verlagshandlung, 1962.

Stern, Fritz Richard. The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in the Rise of the Germanic Ideology. California library reprint series. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

Wehler, Hans Ulrich. The German Empire, 1871-1918. Providence, RI: Berg Publishers, 1993.

Winkler, Heinrich August. Germany: The Long Road West. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Opponents

Blackbourn, David, and Geoff Eley. The Peculiarities of German History: Bourgeois Society and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Germany. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Furet, François. Unanswered Questions: Nazi Germany and the Genocide of the Jews. 1st ed. New York: Schocken Books, 1989.

Kocka, Jurgen. “Asymmetrical Historical Comparison: The Case of the German Sonderweg.” History and Theory 38, no. 1 (February 1999): 40-50.

Meinecke, Friedrich. The German Catastrophe: Reflections and Recollections. Boston: Beacon Press, 1963.

Nolte, Ernst. Die Weimarer Republik: Demokratie Zwischen Lenin Und Hitler. München: Herbig, 2006.

[1] Jurgen Kocka, “Asymmetrical Historical Comparison: The Case of the German Sonderweg,” History and Theory 38, no. 1 (February 1999): 41.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 42.

[5] Ibid., 43.

[6] Ibid., 44.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., 45.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid., 46.

[11] Ibid., 47.

There are also some good lecture notes here: http://www.history.ucsb.edu/faculty/marcuse/classes/133c/133cPrevYears/133c06/133c06l04SpecialPath.htm