In preparation for my Oral Exam on October 28, 2010, I have written down some questions and possible replies about the Industrial Revolution in modern British History.

Bibliography

Some of the important works I’ll draw from are:

- Berlanstein, Lenard R, ed. The Industrial Revolution and Work in Nineteenth-Century Europe. London, [England]: Routledge, 1992.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. The Age of Revolution [Europe] 1789-1848. New York: New American Library, 1962.

- Thompson, Dorothy. The Chartists: Popular Politics in the Industrial Revolution. 1st ed. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984.

- Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Pantheon Books, 1964.

- Thompson, F. M. L. The Rise of Respectable Society: A Social History of Victorian Britain, 1830-1900. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1988.

- Wiener, Martin J. English Culture and the Decline of the Industrial Spirit, 1850-1980. 1st ed. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Questions

How did the Industrial Revolution affect British society and politics?

Changes in Lower Classes

As E.P. Thompson’s book title suggests, the Industrial Revolution created a new socially aware and politically active group, or class of people. And it created more than one. E.P. focuses on the worker class that was established as people became workers in factories. The Industrial Revolution also created a new middle class of merchants and businessmen.

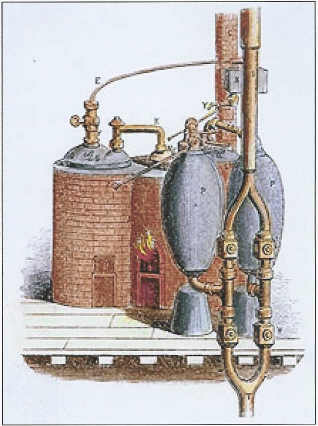

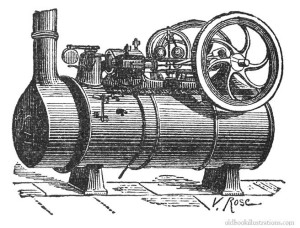

Industrial Revolution also changed trades. The weavers were the hardest hit. Once a respectable and well paid trade, after industry replaced people with machines, weaver trade was poorly paid and dishonorable. Positions opened up for women and children to work in factories. People moved to more urban areas. F.M.L. Thompson argues though, that these modes of urbanization were already in place and were not affected by industrialization.

This bespeaks a fear seen in all levels of society: the fear of change, the fear of technology, the dominance of machine over man.

Organizations Lead to Political Activism

This working class eventually formed unions to deal with issues in the factories, and such organization and collaboration in factory politics spilled out into the politics of government as they eventually sought redresses with Parliament. Dorothy Thompson writes about such a movement known as Chartism, that happened in the 1830s and 1840s. Chartism was a movement of varying and differing causes, with the intent of a better society, fueled by the long unhappy workingmen throughout the country.

Middle Class Changes in Society

The middle classes created their own sphere in English society. Wanting to emulate the aristocracy, they embraced the idea of the gentleman and created a culture of private and public spheres for women and men, codes of conduct and beliefs. Industry began a continual decent in the late nineteenth century as the middle class (the owners of industrial factories, the merchants and businessmen) abandon capitalist notions and seek the leisurely life of the gentleman. One argument is that the decline in British industrialism was a direct result of the middle class emulating the aristocracy instead of overcoming them (socially and politically) (Wiener).

Historians and the Industrial Revolution

How historians view the Industrial Revolution shows how history telling is affected by modern economic, political and social atmospheres. Four phases of interpretation show that the Industrial Revolution was viewed as a negative consequence of human behavior; a cyclical process of nature tied to war and economic challenges; a process for economic growth; and most recently as nothing more than anticipated economic and technological evolution.

Why does E.P. Thompson hate the standard of living debate?

Thompson looks at the standard of living between 1790-1840. The biggest issue is that historians sympathetic to capitalist entrepreneurship used the data to match their conclusions, rather than to discover what was there. (Like looking for red cars and noticing how many there are, to the exclusion of noticing all the other colors.) This issue leads to three other issues with historical the look at the standard of living.

1. Historians did not take into consideration that quantity can increase and quality can decrease at the same time. Economic historians take the rise in wages and goods and deduce that quality of live increases too. Social historians look at the writings about poor quality of life and deduce that material wealth declined as well. Thompson argues that the Industrial Revolution brought increase in material goods (wages, products, etc) but the “well-being” of workers decreased (decreased leisure time, less independence, longer working hours, etc) (211).

2. Taking an average dilutes the actual findings. Adding the stats for all counties and then dividing by the number of counties to find an “average” ignores the discrepancies within the counties. One county may be very rich, another very poor, but combining their info and dividing by their numbers does not provide an accurate description of how those counties actually were (213-214).

3. Quality is subject to interpretation and dependent upon the group you’re looking at (gentlemen, poor, workers, laborers, etc)