I met with my Dissertation adviser last week, and we decided that the topic I had picked really had nothing to do with my dissertation. I don’t know why, but I had always been afraid to just bite off a chunk of the dissertation and give that a go. But after talking with Prof. Deshmukh, it should be quite doable.

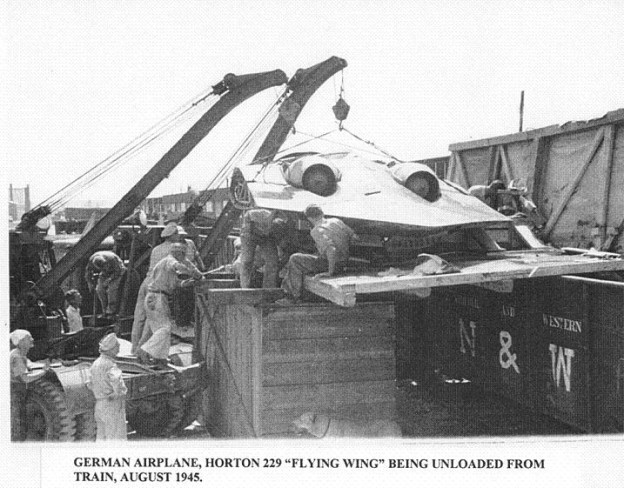

So the dissertation is the Nazi tunnels, and this paper will be an important part of that. One of the two organizations that looked into, and actually built some of the planned tunnels was the Reichsministerium für Rüstung und Kreigsproduktion (RMfRuK, Reich Ministry for Armaments and War Production). This group was headed by Albert Speer, who incidentally was a very interesting man. Anyhow, my paper will now look at the Reich Ministry for Armaments and War Production. It will kind of be an historical overview of the organization and several key players in the building of the tunnels.

As we were discussing each others papers in class last night, the question kept coming around to what is the so what question, or why is this important for us to know. I went last, so we were all ready to just get out of class, and we didn’t really get to that part of mine. Which I’m kind of glad for, since I don’t really have one. Why is this important for us to know? Because it helps us understand the tunnel? Does that work?

At any rate, such is my new topic, it applies directly to my dissertation, and will be part of a chapter that discusses the organizations involved in building the tunnels.

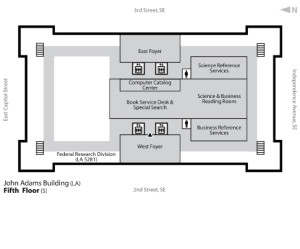

This, of course, means that all of my sources and bibliography need to be redone. I was a bit worried about sources, which is probably why I didn’t want to do the topic. Well, it turns out that Prof. Deshmukh has copies of the indexes to the Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, VA, which are the captures Nazi documents housed at the U.S. National Archives. It just so happens that there are over 1000 rolls of microfilm that reference the RMfRuk (with over 190 being the records of this organization directly)! What a find. Now my extra hours will be spent going over the hundreds of pages of the indexes looking for references to Speer, Himmler, Kammler and tunnels. And then it’s off to the National Archives in College Park, Maryland to look at the actual documents. I have a lot to do before the April 12 deadline of the first draft (which should be as complete as possible).

So, if you didn’t get it yet, here are the steps to doing such a research paper:

- Find an interesting topic. It has to hold your attention, or you will be miserable.

- Talk to your Professors. They’ll point you on the right track for all kinds of things (sources, topic focus, secondary literature, encouragement, etc).

- Find the sources. Best is to find an index or something that describes the sources. For my example, before I even go to the National Archives, I will have a list of specific rolls of microfilm I need, with particular documents I want to look at on the films. Hopefully my bank account can sustain the copies needed, or better yet, I’ll be able to make digital copies.

- Find secondary literature about any aspect of your topic. In my case I need books and articles about Albert Speer, the RMfRuk, Nazi organizations, industrial and economic studies of Nazi Germany, etc.

- Look the the secondary material for insights, information, and most importantly, more sources. I’m now see how important footnotes are, and can see what resources are most often used, what works are most often cited, and who makes what arguments. Harvesting the footnotes for sources is integral in historical research.

- Gather information from primary and secondary sources and make an outline of the argument.

- Write, write, write, and then do some more writing.

So, I am back to step 3, finding the sources. I’m going to the Archives on Friday. Wish me luck!