So, what are the big issues in modern French History?

- Fears of change. Periphery versus the national (Paris). Modern versus traditional. New versus old forms of society, government, culture. National versus local.

- Social importance and role of individuals. Individual versus community versus monarchy.

- Vitality and virtue of French. Really comes into play during Dreyfus affair and national result indicating lowering birth-rate. Escalated through the two World Wars, and can be seen as the cause of issues with Algeria, and blossoms again in their search for vitality in nuclear power.

- Political troubles. Around eleven (11) major changes in political power from 1780-1960, contrasted with other European and world powers (USA – 1, England – 1, Germany – 5)

I’ll look at the following:

- Republicanism and Nationalism

- Antisemitism

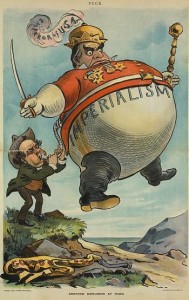

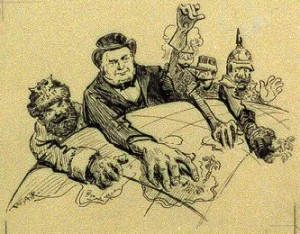

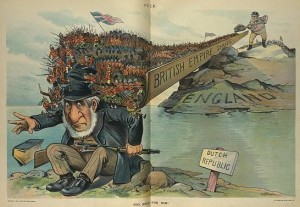

- Colonialism

- World War I and World War II

- Post-war national identity

Referencing some of these books:

- Caroline C Ford, Creating the Nation in Provincial France: Religion and Political Identity in Brittany (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1993).

- Christopher E Forth, The Dreyfus Affair and the Crisis of French Manhood, The Johns Hopkins University studies in historical and political science 121st ser., 2 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004).

- Sudhir Hazareesingh, From Subject to Citizen: The Second Empire and the Emergence of Modern French Democracy (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1998).

- Gabrielle Hecht, The Radiance of France: Nuclear Power and National Identity After World War II, Inside technology (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1998).

- Alistair Horne, A Savage War of Peace: Algeria, 1954-1962 (New York: Viking Press, 1978).

- Eric Thomas Jennings, Vichy in the Tropics: Pétain’s National Revolution in Madagascar, Guadeloupe, and Indochina, 1940-1944 (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2001).

- Maurice Larkin, France Since the Popular Front: Government and People, 1936- 1986 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988).

- John McManners, Church and State in France, 1870-1914 (New York: Harper & Row, 1972).

- Philip G Nord, The Republican Moment: Struggles for Democracy in Nineteenth-Century France (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995).

- Robert A Nye, Crime, Madness, & Politics in Modern France: The Medical concept of National Decline (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1984).

- The Sorrow and the Pity Chronicle of a French Town During the Occupation = La Chagrin Et La Pitie: Chronique D’une Ville Francaise Sous L’occupation (Milestone Film & Video ; [New York], 2000).

- Robert O Paxton, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940-1944, Columbia University Press Morningside ed. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982).

- Pamela M Pilbeam, The Constitutional Monarchy in France, 1814-48, Seminar studies in history (Harlow, England: Longman, 2000).

- David Prochaska, Making Algeria French: Colonialism in Bône, 1870-1920 (Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

- Henry Rousso, The Vichy Syndrome: History and Memory in France Since 1944 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1991).

- Rebecca L Spang, The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2000).

- Eugen Joseph Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870-1914 (London: Chatto & Windus, 1977).

- Eugen Weber, The Hollow Years: France in the 1930s, 1st ed. (New York: Norton, 1994).